All the streams that bursts from the Kumaon and Garhwal Himalaya unite to become Ganga - the River Ganges. But one of Ganga's sources is revered above all the rest. It's Gaumukh, the place where the river emerges from the snout of the Gangotri Glacier.

We set off for Gaumukh at lunchtime.

“Please be quick and careful,” said a sign.

Gaumukh is the place where the Bagirathi River emerges from beneath a glacier. It is held to be the main source of the Ganga. The name means "cow's mouth."

The path to Gaumukh was engineered across a cliff of brown granite, high above the riverbed. Its inside was a ledge hewn from the cliff; its outside hung over space and the river, cantilevered from the rock on wooden struts. The steel railing along its edge was bent and torn where it had been struck by rocks falling from the crags above. The path was almost, but not quite, wide enough to allow a person and a laden pony to pass one another with equanimity.

We soon met the first downward-bound ponies, and we passed them without equanimity, shamelessly forcing them to the outside edge unless their cargo happened to be human. They were the jetsam of a trekking group that had shared our hotel, paid off like spent rocket boosters. Some of them bore pilgrims who had abandoned their journey. The casualties were of all ages and shapes and sexes, grey-faced from the altitude and stoical in defeat.

We were finding the going hard enough ourselves. The path was gentle but the air was thin and our sacks were heavy with camping equipment and food. Julia was fresh from Scotland, unused to the altitude or to heavy loads, and my own acclimatisation had been sweated out of me in Delhi.

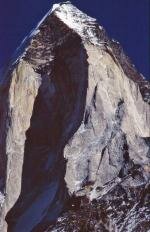

It was not far from Gangotri to Gaumukh, but we intended to spend a couple of nights on the journey so that our bodies could adjust themselves to the falling air pressure. Then we would walk on up the glacier above. It was a cul-de-sac, but we wanted to get close to the high peaks before we continued our journey west.

We stopped at a collection of canvas shelters beside a pine copse. Tumblers of sweet tea arrived. Ponies foraged in the woods around us, harassed by their minders. Exhausted pilgrims lay under blankets in the various shelters. There were forty-five of them, the chai-wallah said. We thought it best to pitch our own tent.

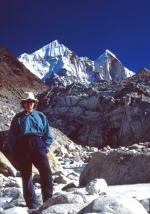

The pilgrims left camp before dawn. We started rather later, and trudged slowly under our big packs. The narrow gorge of the Bhagirathi became a wide vale. From time to time, when I found myself ahead of Julia, I would stop for a moment with a ski pole propped under my sack to lift the weight from my shoulders and hips. After a while we stopped for a proper rest.

A man approached slowly up the path. He was wearing a schoolmasterly brown jacket and had a little nylon sack on his back. He might have been in his sixties.

“Excuse me,” he said. “Why are you resting here?”

We walked on through the forty-five pilgrims. They were on their way home, keen to get down to the encampment in the woods before nightfall. Some of them had reached the Ganga’s source; many had not.

“You won’t stay at the Rest House?” I asked a man dressed in a thin orange anorak and a blanket.

“Too much cold. Too thin air.”

No one had explained to him that it takes time to adjust to the thin air.

The Rest House stood on the flat valley floor beneath the glacier’s moraine. Above, miles distant, huge granite walls glowed pink in the evening sun. There were four people in the Rest House when we arrived; an Irish couple, an Australian and a Canadian. They had all been to Gaumukh. Later on, we were joined by the Indian man we had met on the track and later still, long after dark, a New Zealander came in. He had tried to reach the place called Tapovan, a green oasis above the glacier. He had not succeeded.